Paragliding in Alaska began in the mid-1980s when Vern Tejas and Harry Johnson of Genet Expeditions returned from guiding a climb on Aconcagua in December of 1985 or 1986. They brought back two French-made “parapentes” purchased from a German pilot they'd seen fly down a small mountain overlooking Punte Del Inca. They knew they had to do it, and after the pilot successfully flew from Aconcagua he sold them the wings. Instructions were brief, and given in limited English. They understood: “right, go right, and pull both, stop.” The second procedure was best performed near the ground.

Thus instructed and equipped they went to Hatcher Pass to teach themselves to fly. In Vern Tejas's words: “Time after time we ran down the hill to the NW of the A-frame with a wad of nylon and lines following behind. Proper layout of the canopy was lost in the translation. However in what was to be my last attempt, whilst in midstride, I broke through the snowcrust and pitched head long down the slope. The extra acceleration along with quick extension of my arms (to save my face) was just the ticket. With a loud pop the canopy fully inflated and drug me kicking and screaming away from the hill. Excitedly I loosed a non-stop string of expletives as I flew over Harry's head and proceeded to learn the art of landing, fortunately on snow.”

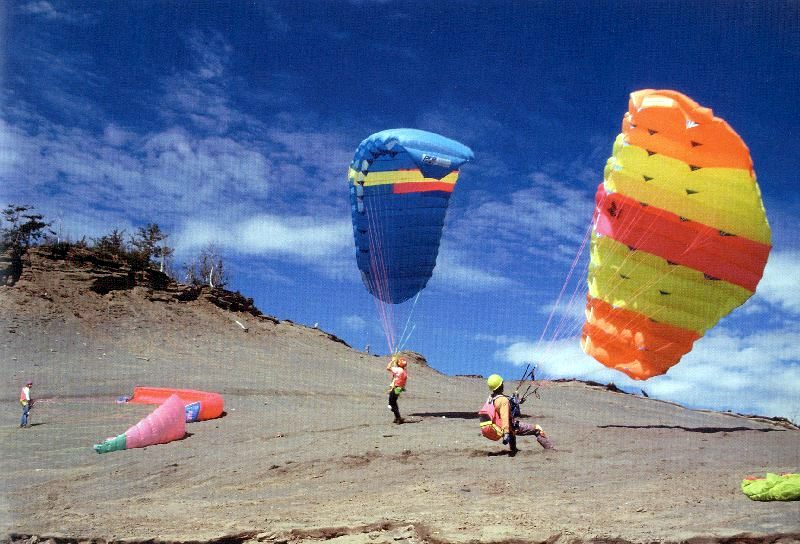

That summer at Hatcher Pass they introduced paragliding to other guides at Genet Expeditions, including Marc Phillips, Clark Saunders, and Norma Jean Saunders. These first “para-sails” were tiny, perhaps a third the size of today's wings, square in shape, with cells so large “you could drive a snow machine through.” With glide ratios of around 2.5 to 1 they “flew” in a controlled plummet, the idea being to provide a fun, less tiring way for climbers to descend mountains. Paragliding spread through the climbing community, first in France where climbers developed it in the late 1970s and early 1980s, and in North America a few years later, largely though friends teaching friends. This teaching, such as it was, tended to be very brief. Clark Saunders recalls his as: “Grab the webbing and run like hell.” “When you get near the ground yank on these lines.” Many times the lesson consisted of a demonstration flight followed by the command; “Now you do that.” Steering towards snow patches was one of the only safety measures known. If there wasn't snow around, “brace for impact.”

Soon after this summer American alpinist Jon Bouchard began producing copies of French ITV wings, which he sold under the brand Feral Wings for a grand apiece. Some came with a sewn-on skull and crossbones patch, and a warning that “you will probably die doing this.” Harry Johnson bought several Feral 7-cell, 8-cell, and 9-cell wings and Genet's guides continued to spread paragliding through the Alaskan climbing and skiing community, Vern Tejas being the most active teacher. Students got their first taste of flight on Feral 7-cells at Hatcher Pass, Alpenglow, the Don Sheldon Amphitheater at the Ruth Gorge, and other steep hills with very nearby LZs. Others taught themselves completely on their own.

In 1988 Clark and Norma Jean Saunders moved temporarily to Point of the Mountain, Utah. They met Fred Stockwell and bought some of his new Harley brand of paragliders, and began to learn that “up” was a possible direction to travel in a paraglider. Fred Stockwell had been involved in forming a paragliding organization in England and took the lead in forming one in the United States. Clark helped him and a few others form the American Paragliding Association, and they began working on an instruction manual with Dennis Pagen. They attended a USHGA board meeting in Boulder, Colorado to propose that hang glider and paraglider pilots had a common interest and should get along and work together. They hoped to get coverage under USHGA's liability insurance, which would be crucial to becoming legitimate users of many sites. However, to say their proposal was not well-received would be putting it mildly. In fact some members greeted it with open hostility and profanity.

By contrast, the actual hang gliders in Alaska were welcoming to paragliders. The local USHGA club, the Alaskan Sky Sailors Association, had formed in 1973 or 1974 and for a time had over a hundred active members flying at Hatcher Pass, Eagle River, Girdwood, Fairbanks and other places in large numbers. A few were national-class pilots. Kincaid, Baldy, Switchbacks, and Summit Lake were all pioneered by hang gliders. Members shared site information and safety insight with the new guys, and some took up paragliding or converted to it. Jeff Bennett was particularly supportive, a rich source of thermaling and cross-country wisdom even before he took up paragliding and set a standard for thermal skill rarely matched anywhere.

After being rebuffed by the USHGA, the APA began the long, hard process of obtaining insurance on their own. Clark Saunders agreed to become Regional Director for Alaska, and moved back in 1989, now an official APA instructor, one of the first in the U.S. He began Raven Adventures Paragliding to instruct and sell equipment, and helped organize the Arctic Air Walkers as a club under the APA. The first meeting was held in June of 1989, upstairs at REI. Bruce Hamler, who later instructed many Alaskan pilots, worked there and secured the location, which was used for a number of years. The Arctic Air Walkers is the oldest organized paragliding club in the United States, and when the paragliding eventually did join the USHGA in 1991, the Arctic Air Walkers was the first charter club of paragliders accepted. For political reasons, the first three chapter numbers were given to others to “keep the peace” between the northwest states and Utah pilots. One particular club wanted the status as #1, and from Clark Saunders' point of view, the important thing wasn't the chapter number but the benefits of membership!

While none of this is ancient history, the rapid evolution of paragliding technology can make it seem that way. Early paraglider pilots on their 7-cells never even contemplated doing a 360 degree turn - you couldn't possibly get far enough from the ground on such a wing, for what would be a senseless maneuver anyway. Within ten years of the introduction of Feral wings, hundred-mile flights were made on paragliders. For a while, new wings went obsolete as fast as computers. Yet, amazingly enough, there were soaring flights in the early days of Alaska paragliding. Bob French actually went up in a thermal for several seconds flying a 7-cell after ski launching the south side of Manitoba Peak on a warm spring day and flying over a huge patch of bare ground. It must have been one strong thermal to lift a wing that got a 3 to 1 glide on a good day! This is perhaps the only thermal soaring flight recorded in a 7-cell; thermals weren't yet even a concept for paraglider pilots so Bob kept flying in a straight line out the other side.

The next generation of wings could ridge soar - in a wind coming up a steep slope at close to the flying speed of the glider. Clark and Norma Jean Saunders would soar Bird Ridge in their Harley 280s. They needed about an 18 mph wind over the top to soar, which translated to a 25 mph wind or higher at the LZ along Turnagain Arm. A flying speed of about 22 mph made for a very narrow flying window! The LZ was in the rotor zone, fortunately these wings were nearly impossible to collapse.

Brook Goss set some sort of record by soaring above the Arctic Circle for more than an hour in about 1989, when he was working at Pump Station#2 on the Alaska

As the focus of paragliding changed from descent to soaring its appeal broadened beyond the climbing and adventure community, and easily accessible sites have become critical to the sport in its present form. Thus, the history of paragliding is also the history of its flying sites. Becoming legitimate users of Hatcher Pass, Chugach State Park, Chugach National Forest, and Alyeska Resort was not easy, short, or guaranteed. In the late 1980s the APA didn’t yet have insurance, which complicated efforts. Hatcher Pass came easiest. Ranger Pat Murphy, who passed on several years ago, was always supportive of paragliding and worked with Clark Saunders and the Arctic Air Walkers to gain legal use of Hatcher Pass. He and then-State Park Director Dale Bingham allowed Clark to instruct there for a couple years without the insurance question being settled.

Around this time Clark Saunders was working for the Rental Shack at Alpenglow. Mountain managers Eric Fugelstadt and Dave Hendrickson got hooked on paragliding, and their support made it possible to obtain permission for lift-served paragliding at Alpenglow, which was possibly the first ski area to allow paragliding in the United States. A contingent of ski-launching pilots flew there on nicer winter days. No need to pack up after a flight, pilots could just bunch up the wing, toss it over their shoulder, and ride back up the T-bar. Roy Warren had over fifty flights before ever foot launching (from an advanced site in Oregon at that).

Alyeska was the most difficult site to open for flying. Even with Clark Saunders' considerable lobbying skill in the forefront it took years of effort to obtain lift-served flying there. The resort leased the upper mountain from the National Forest Service, the LZs on the valley floor were Municipal land, so permission had to be obtained from three entities. The manager of the Glacier Ranger District of the Chugach National Forest was not interested in dealing with another dangerous “fad” sport. He'd been bothered by issues arising from a past hang glider crash and a few obnoxious skydivers, and paragliding probably looked to him like a combination of the two sports. Clark Saunders and Barney Griffith met with the Girdwood Board of Supervisors and gained public approval from the locals, with some stipulations as to where and how paragliders would fly in Girdwood, but the Glacier District manager still didn't want to deal with another “nuisance” as he approached retirement. He wrote to Clark that “though we would love to embrace this new sport, we are unable to without a minimum of $300,000.00 third party liability insurance”, believing that this was out of reach for paragliders. He did not know that APA was closing in on obtaining just this type of insurance. Clark wrote him back asking if he would approve paragliding if insurance was obtained. He responded - Yes, of course. A few months later Clark presented proof that the APA had been able to obtain that exact amount of insurance, and paragliding was approved on the upper mountain of Alyeska.

Clark went to work for Alyeska Resort and eventually obtained approval from John Hizer, the Mountain Manager, for lift-accessed flying. He established the minimum criteria and rules and regulations that would keep the Japanese owners, local small airplane pilots, and the skydiving club at ease with paragliding at the resort while expanding flying privileges. Later Clark approved commercial tandem paragliding at the resort.

Chugach State Park fell in line once the insurance and certified instruction criteria were met. Dale Bingham and Pat Murphy worked closely with the club to open up State Parks to legalized paragliding under the same conditions they'd approved at Hatcher Pass. Most of the peaks in Chugach State Park near Anchorage like Blueberry Bump, Bird Ridge, Bear Mountain, Eklutna ridge were flown early on. Baldy, with its low glide angle, had to wait for glider performance to improve. The first flights from the top were flown in spring of 1990. Pilots landed at the tower bench where the current launch is because they couldn't make the glide out to the gravel pit LZ by Spenard Builders Supply. The first flights from top to bottom were in 1991. Paragliders first flew from the bench in 1996 after further glide improvements, and it became “the” Anchorage site, providing drive-up thermal soaring and three possible directions to fly cross-country.

In spring of 2002 rumors about a Fred Meyers being built in the gravel pit finally came true. The Arctic Air Walker looked for an LZ on adjacent Municipal land, which was undeveloped but also wooded. Bill Mendenhall had contacts with the administration and took the lead in making this tough sell to the city. A proposal to lease once-cleared land behind the old LZ and re-clear it of the alders and cottonwood saplings that used to snag the occasional too-low paraglider was in the final stage of approval when the city reversed course. Then Parks and Rec proposed clearing land for a snow-dump adjacent to the Harry McDonald Memorial Center and offered it as a possible LZ. A committee of Arctic Air Walkers and then-president Jack Brown went through a lengthy back-and-forth process of working out an agreement with the city to gain use of the proposed field, which predictably took longer than predicted to develop. In the meantime, paragliders landed along Springbrook road on a strip of land cleared for a construction project that hadn't come to pass. It was narrow and squirrely, and pilots were relieved when the excellent Harry Mac LZ opened in 2008.

While all this was going on, private development threatened access to launch and the popular Baldy trail. Arctic Air Walkers were central in persuading the Municipality to trade land for permanent, legal access to launch and Baldy, also benefitting the much more numerous (but unorganized) hikers and other outdoor recreationalists. Kincaid required a similar amount of work to keep open since the launch is on city land and the airspace is controlled by the airport tower. The lesson here, frequently learned over the years, is that launching and landing on public land and flying in public airspace anywhere near a road and a population center is usually a privilege fought for, not a right granted.

Compiled by Adrian Beebee June, 2010